In Brief

- In an expanding universe, when we look at objects 1 billion light years away, we see what they look like LESS than 1 billion years ago. And in order to see what they look like currently, we will need to wait for MORE than 1 billion years.

- Even though we say the expansion of the universe is accelerating, the “intrinsic expansion rate”, rate at which the space is increasing at unit distance is actually slowing down.

- Because the “intrinsic expansion rate” is slowing down, light emitted from stars that are currently moving away from us at the speed of light can still be observed in the future.

- Contrary to common misconception, even in the distant future when all distant galaxies have moved outside of our cosmic event horizon, they won’t simply disappear in the sky, but instead become frozen images with the light from them more and more red-shifted.

Introduction

Most lectures about cosmology I’ve seen like to start from general relativity. While it is helpful to have the mathematical background to understand the details of our current cosmological model, I find it much more important and usually more effective to first think about the conceptual problems, to shift our world view to the cosmological perspective. Some of the most counter-intuitive things can happen in the expanding universe, and we can understand them without knowing general relativity. We only need to assume some basic properties about the expanding universe. To focus our attention on the concepts in this chapter, I will treat the expanding universe as a theoretical construct without worrying too much about the proofs. We will leave the observational evidence for future chapters.

Properties of An Expanding Universe

- The amount of space itself is increasing with time.

- Astronomical objects are moving relative to their local space.

One way to imagine this is to think of space as a rubber sheet. It can stretch and contract while the objects are moving on it. The fact that space can stretch and contract induces an apparent velocity even when the object is not moving relative to the local space by itself. Imagine two fixed points on the rubber sheet. The stretching or contracting of the rubber makes one move away from or towards the other. On top of this apparent motion, the relative movement with respect to the local space induces the “local velocity”. And the total effective velocity of an object seen from another will be the addition of these two motions.

On very large scales, the local motion is negligible in comparison to the apparent motion induced by the expansion of the space itself.

Definitions of distances

In an expanding universe, because the distance changes with time, the distance between A and B at time 0 is no longer the same as the distance between them at time t, and these distances are not the same as the distance traveled by someone going from A to B from time 0 to time t. To describe the concept of distance in an expanding universe, we need the following definitions.

Co-moving Distance

To disentangle the effects of property 1 and property 2, we construct so-called “co-moving coordinates” to mark the expansion and contraction of the space itself. The co-moving distance is the distance measured on this coordinate system and is therefore fixed relative to space itself. The lattice spacing between the coordinates indicates how space itself is changing in time. And the change in the co-moving coordinates indicates a real motion relative to the local space. We denote the co-moving coordinates with the letter \(r\) and the lattice spacing with \(a(t)\), as a function of time. The co-moving distance will be denoted as \(D_{C}\).

Proper Distance

Proper distance is the “real” distance between two objects, i.e. the lattice spacing times the co-moving distance between these two objects. In Fig. 1, the co-moving distance between coordinates 1 and 2 is always 1, but the proper distance \(a(t)\) changes from 1 unit to 3 units because of the expansion. The proper distance will be denoted as \(D_P\).

Notice that for objects fixed in space, because it is easy to convert between the co-moving distance and the proper distance, most of the time it’s not necessary to specify which one we are talking about. For example, “the distance between A and B” can be understood as either the co-moving or the proper distance, and it’s easy to work out one from the other. In that case, we will just say “distance”.

Traveling Distance

This introduces the first thought experiment: in a universe where space varies with time, the proper distance an object traveled from point A at time \(t_{A}\) to point B at time \(t_{B}\) is in general not the same as the proper distance at time \(t_A\) nor \(t_B\).

Let’s say space is expanding. As the object travels from A to B, the space in front of it is constantly increasing, so that the distance it has to travel to reach B is certainly larger than the original proper distance at time \(t_{A}\). At the same time, the space behind it, i.e. the space it has already traveled, is also constantly expanding, so that the proper distance at time \(t_{B}\), namely \(D_{P}(t_{B})=a(t_{B})\|r_{B}-r_{A}\|\), is larger than the distance it traversed. So in this case we have \(D_{P}(t_A)<D_{T}<D_{P}(t_B)\), where we denoted the traveling distance with \(D_{T}\) and the proper distance between AB at time \(t_A\) and \(t_B\) with \(D_{P}(t_A)\) and \(D_{P}(t_B)\).

Once you figure this out, it’s easy to understand the following seemingly counterintuitive phenomena:

- When we look at objects that are currently 1 billion light-years away, we see what they were like LESS than 1 billion light-years away.

- For us to see what objects that are currently 1 billion light-years away look like, we will have to wait MORE than 1 billion years.

Whenever we talk about distance, we need to understand which distance at which time we are talking about. For example, when we say that we can see light from objects 28 billion light-years away even though the universe is only 13 billion years ago, what we mean is that we can see light emitted 13 billion years ago from objects that were less than 13 billion light-years away from us when the light was emitted, but now are 28 billion light-years away from us. We don’t currently see the light currently emitted by objects that are currently 28 billion light-years away.

Understanding Expansion

The Unfortunate Definition of “Accelerating Expansion”

Whether the expansion of the universe is accelerating or decelerating is defined by \(\ddot{a}(t)\). This is defined from the perspective that if we observe the space expansion between two fixed points on the co-moving coordinate system, whether we see the rate of space added is increasing or decreasing. But if we think about this for a minute, we will realize that more spaces may be added later, simply because there are more spaces between the two points later. In other words, the textbook definition of “accelerating expansion” is the “apparent accelerating expansion”.

This definition is very unfortunate, since it does not capture the “intrinsic expansion rate” of the universe and thus induces a lot of confusion, especially when we consider the event horizon of the universe, as we will see below.

Intrinsic Expansion Rate: the Hubble Parameter

To get the “intrinsic expansion rate”, we need to remove the dependence on the changing distance. This can be achieved by dividing the apparent velocity of a distant co-moving object by the proper distance in between:

\[H=\dfrac{r\dot{a}(t)}{ra(t)}=\dfrac{\dot{a}(t)}{a(t)},\]

where \(\dot{a}(t)\) is the time derivative of \(a(t)\). For those interested, Young’s modulus in solid-state physics is defined in a similar way to get rid of the length dependence so that it reflects the property of the material.

In other words, the Hubble parameter gives the true expansion rate.

To make it clearer why using \(\ddot{a}(t)\) to understand expansion is a bad idea, think of it this way: let’s say the Hubble parameter is not changing with time, which means the characteristic expansion of the universe is not speeding up nor slowing down. But since at a later time, \(a(t)\) itself becomes larger, the induced apparent velocity at that larger proper distance will become larger, and thus \(\ddot{a}(t)>0\), and we get the conclusion that the universe’s expansion is “accelerating”. That “acceleration” is relative to the coordinate system set up from the very beginning. If instead you compare the expansion of space now to the expansion of space between objects with the same amount of proper distance in between a long time ago, the expansion can be slower.

How does \(a(t)\) change if the intrinsic expansion rate is constant? We can solve \(H=\dot{a}(t)/a(t)=\beta\) to get \[a(t)=e^{\beta t}.\] In other words, at a constant intrinsic expansion rate, \(a(t)\) should be increasing exponentially. Therefore, any slower change of \(a(t)\) corresponds to a decrease in the intrinsic expansion rate. One can check this easily with \(a(t)=t^2\). Obviously \(a(t)\) increases at an accelerating rate, but the “intrinsic expansion rate” \(H=\dot{a}/a=2/t\) is actually decreasing. Said in another way, a constant \(H\) corresponds to an exponentially increasing \(a(t)\), while a decreasing \(H\) corresponds to slower increase in \(a(t)\).

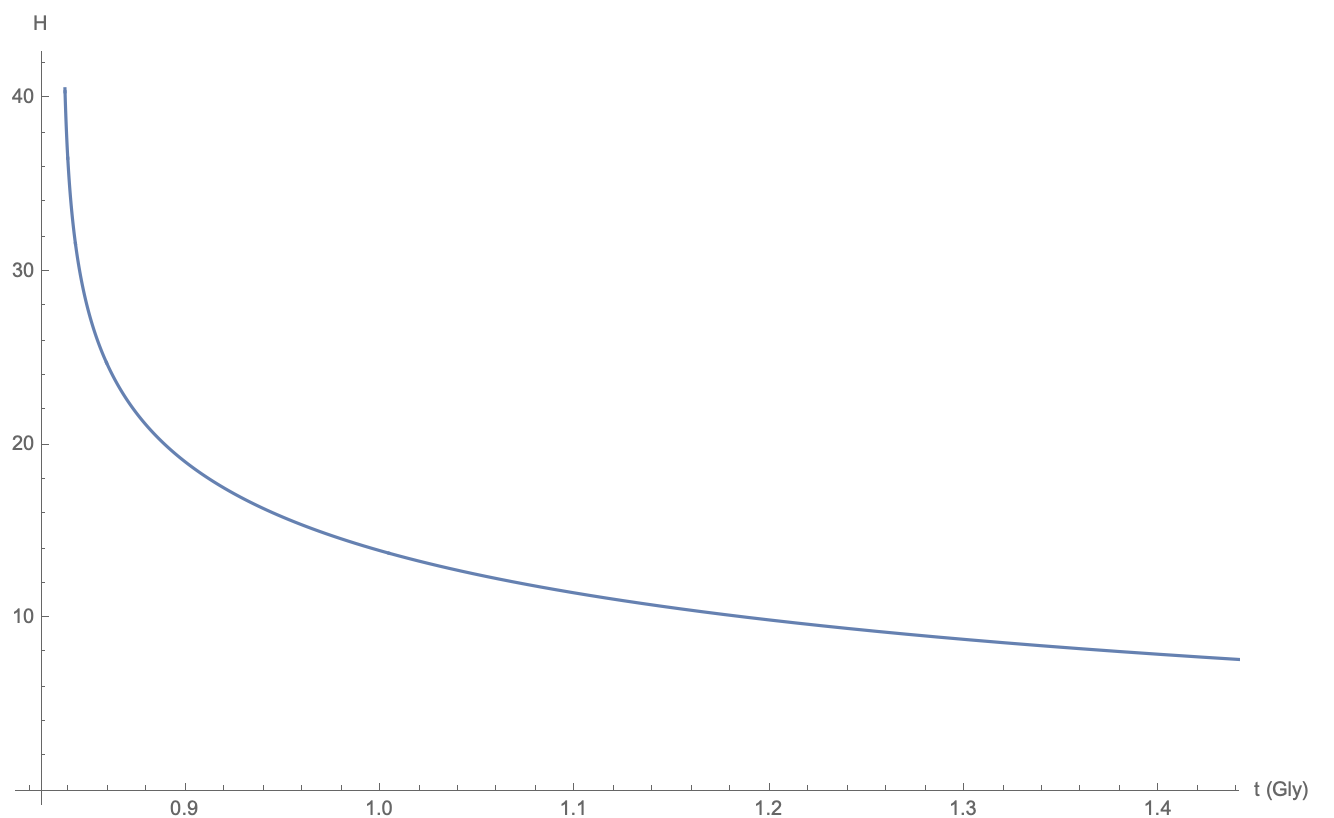

The Hubble parameter in our standard cosmology model changes as follows. It decreases quickly in the beginning, and then gradually approaches a constant. So initially \(a(t)\) increases at a rate slower than exponential, but eventually, \(a(t)\) expands exponentially.

How the Expansion Affects Our Observations

Hubble Distance

Hubble distance is defined as the distance at which the receding velocity is the speed of light:

\[D_H=\frac{c}{H}.\]

However, due to the space expansion, we can see objects that are currently moving with speed above the speed of light, beyond the Hubble distance, as explained below.

Cosmic Event Horizon

The event horizon is the distance at which the photon emitted now will never reach us in the infinite future. One might naively think that this distance is the Hubble length. After all, the objects beyond the Hubble length are leaving us at speeds greater than the speed of light, so of course, their light can never reach us! Well, think again.

We will be able to see light emitted from some objects outside of our Hubble Sphere, thanks to the slowing down of the intrinsic expansion rate \(H\)!

A Detour

This is very counter-intuitive. Before we go into the correct explanation, I want to spell out a couple of common traps people tend to fall into when thinking about this problem:

As hinted above, people assume that just because the photons emitted from those objects are now apparently moving away from us, and the expansion is “accelerating”, there’s no way that the light emitted from these objects will reverse their course and come towards us.

We already explained what “accelerating expansion” really means. So the above assumption translates to: because \(a(t)\) is accelerating, the apparent velocity of the object can only increase. The implicit assumption for that statement is that the apparent velocity of the object only depends on how \(a(t)\) changes. Is that true? No. The apparent velocity of the photon is composed of two parts:

the apparent velocity induced by the expansion of the universe, which is \(r\cdot \dot{a}(t)\), depends on both how \(a(t)\) changes and how its co-moving coordinates \(r(t)\) changes;

the local velocity of the photon, which is c.

The apparent velocity of the photon is therefore \(r(t) \cdot \dot{a}(t)-c\).

Just because at one moment this value is positive (moving away from us), does not mean that it will stay that way. At the same time that \(\dot{a}(t)\) is increasing, the co-moving distance \(r\) is decreasing because the photon is locally heading in our direction. The apparent velocity can potentially decrease if the decreasing \(r\) brings down the total apparent velocity, even though \(\dot{a}(t)\) is increasing.

Once we understand how the apparent velocity also depends on the decreasing co-moving distance, people might assume that just because the apparent velocity might start decreasing, that will guarantee the photon can reach us.

Unfortunately, the apparent velocity of a photon can slow down and never get to the point where the apparent velocity is flipped. It’s hard to show this without invoking some math, but one can conceptually understand that the changes of \(r(t)\) and \(\dot{a}(t)\) can result in the apparent velocity \(r(t) \cdot \dot{a}(t)-c\) decreasing but never reaching zero.

Explanation

It’s easy to see that reasoning using the apparent velocity is difficult and error-prone. Our first instinct and intuition lead us that way, probably because we are so used to thinking about motions in terms of how velocity changes. However, the dynamics in an expanding universe are more complex, because the velocity induced by the expansion is location-specific (it’s a function of relative distance), while the other local velocity is constant relative to space. This makes it very hard to imagine and reason about how the apparent velocity changes, since at the next moment, the location changes and the location-induced velocity changes.

Instead of thinking in terms of velocity, let’s think in terms of the co-moving coordinates since it’s easier to see the effect of the local motion relative to this coordinate system.

During a small time interval \(dt\), the photon travels a distance \(cdt\) in space, which gives \(dr = c dt/a(t)\) in terms of the co-moving distance. The proper distance at a cosmological time \(t\) corresponding to the total co-moving distance that can be traversed from time \(t\) to the infinite future is the definition of Event Horizon:

\[R_{EH} = a(t)\int_{t}^{\infty}\dfrac{c dt}{a(t)}.\]

When the universe is expanding at a constant intrinsic rate, \(a(t)=e^{\beta t}\), we have

\[R_{EH} = \dfrac{c}{\beta} = D_{H}.\]

The Hubble Sphere coincides with the Event Horizon. It’s easy to understand then if the “intrinsic expansion rate” is not constant, but instead slowing down during the time the photon was traveling to us, it will be able to cover more ground, and therefore the Event Horizon will be larger than the Hubble distance.

As mentioned before, the intrinsic expansion rate of our universe is slowing down, resulting in the fact that we can observe objects outside of our current Hubble Sphere, even though the expansion rate as measured by \(a(t)\) is speeding up.

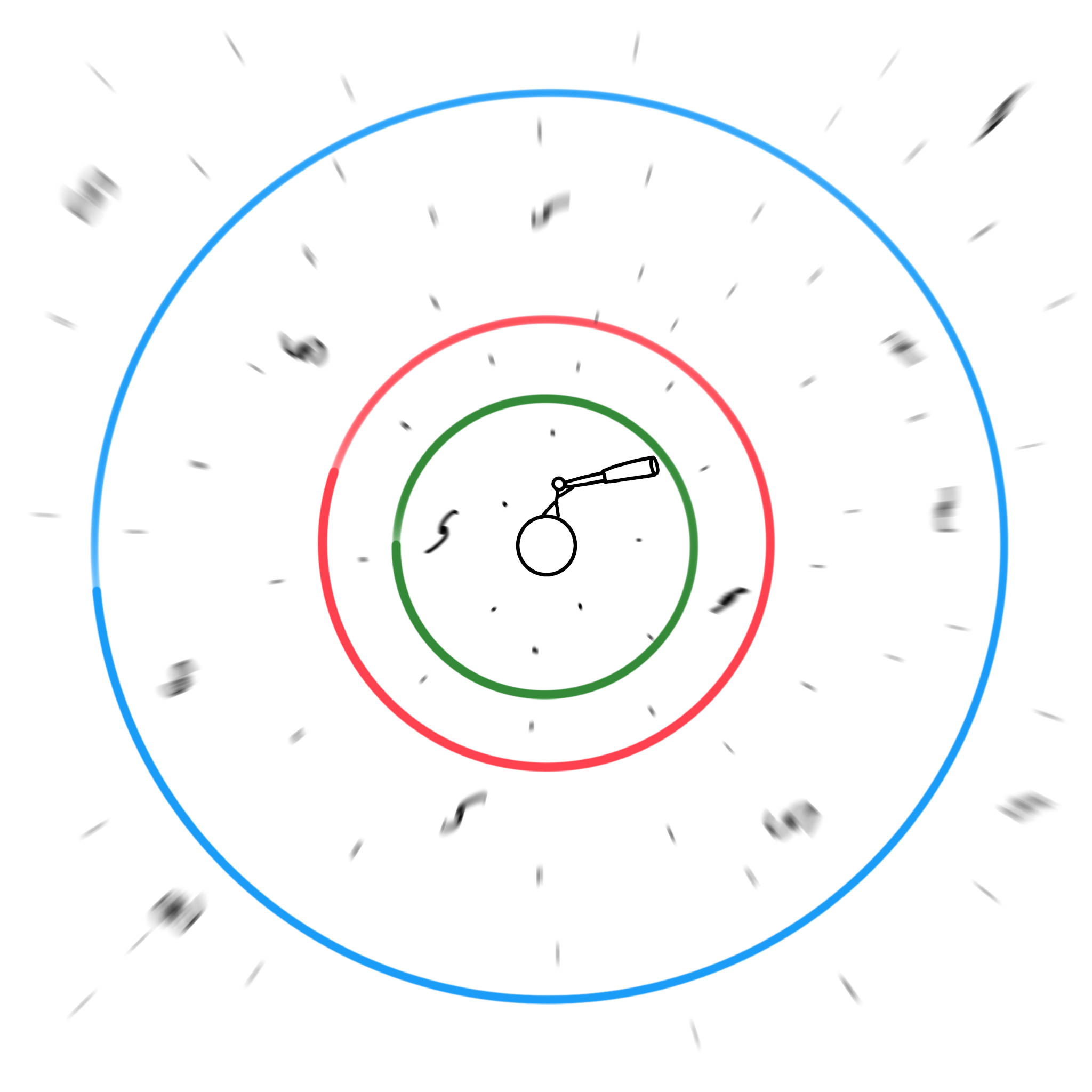

Particle Horizon

The particle horizon describes the furthest distance we can see right now. And because it takes photon time to reach us and we are looking back in time as we look deeper into space, it should not be a surprise that we can see things that are currently beyond our current Hubble sphere and our current event horizon.

It’s very important to stress that we are not seeing what these objects look like right now since it takes time for the photon to travel to us. We are only seeing them as their younger selves when the distance to them was different.

Confusingly, the particle horizon is not defined in terms of the co-moving distance of these objects, which never changes, nor is it defined as the proper distance at which the photon was emitted, but instead the current proper distance of these objects, even though we are not seeing them at the current proper distance right now:

\[R_{PH} = a(t)\int_{0}^{t}\dfrac{c dt}{a(t)}\]

Observable Universe

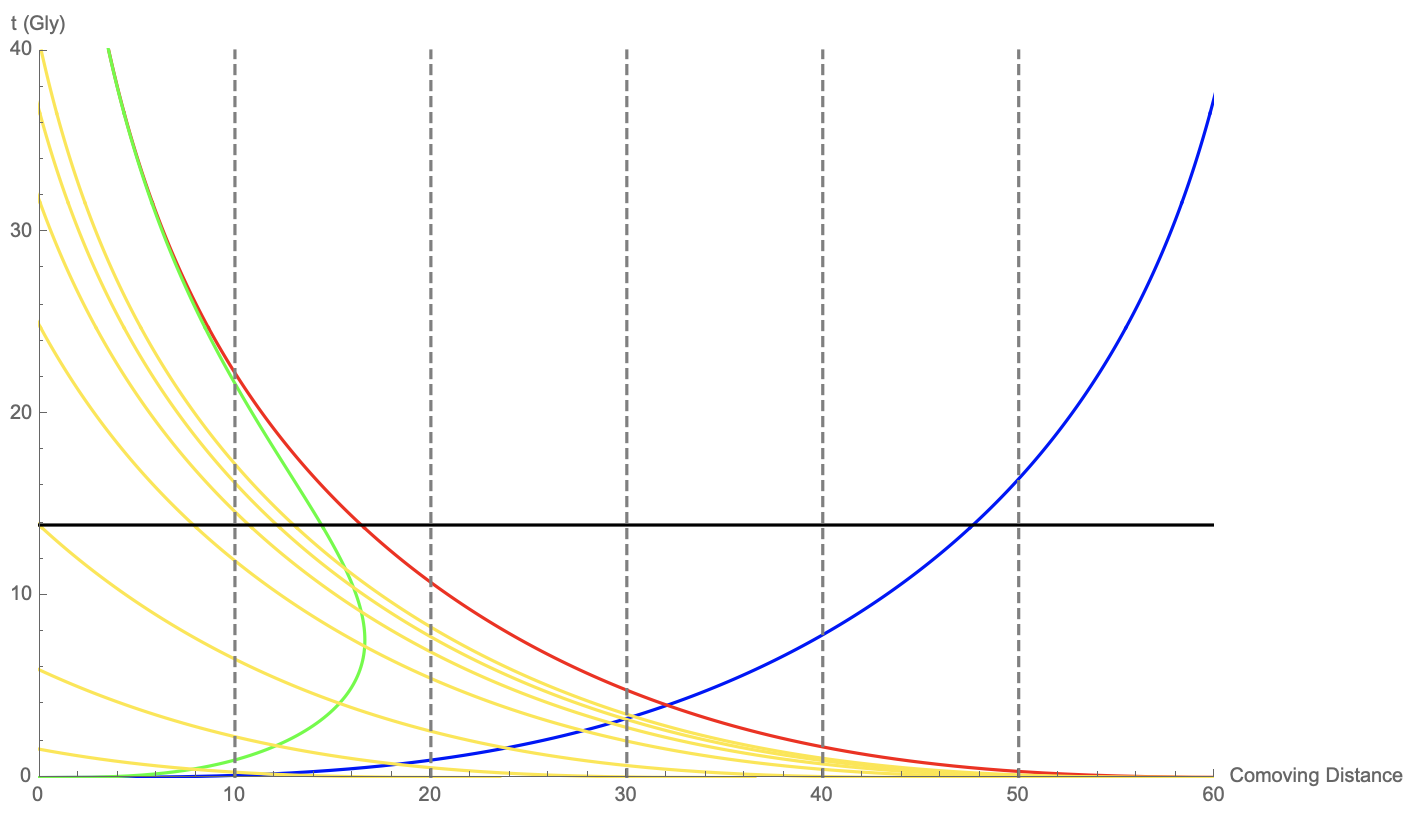

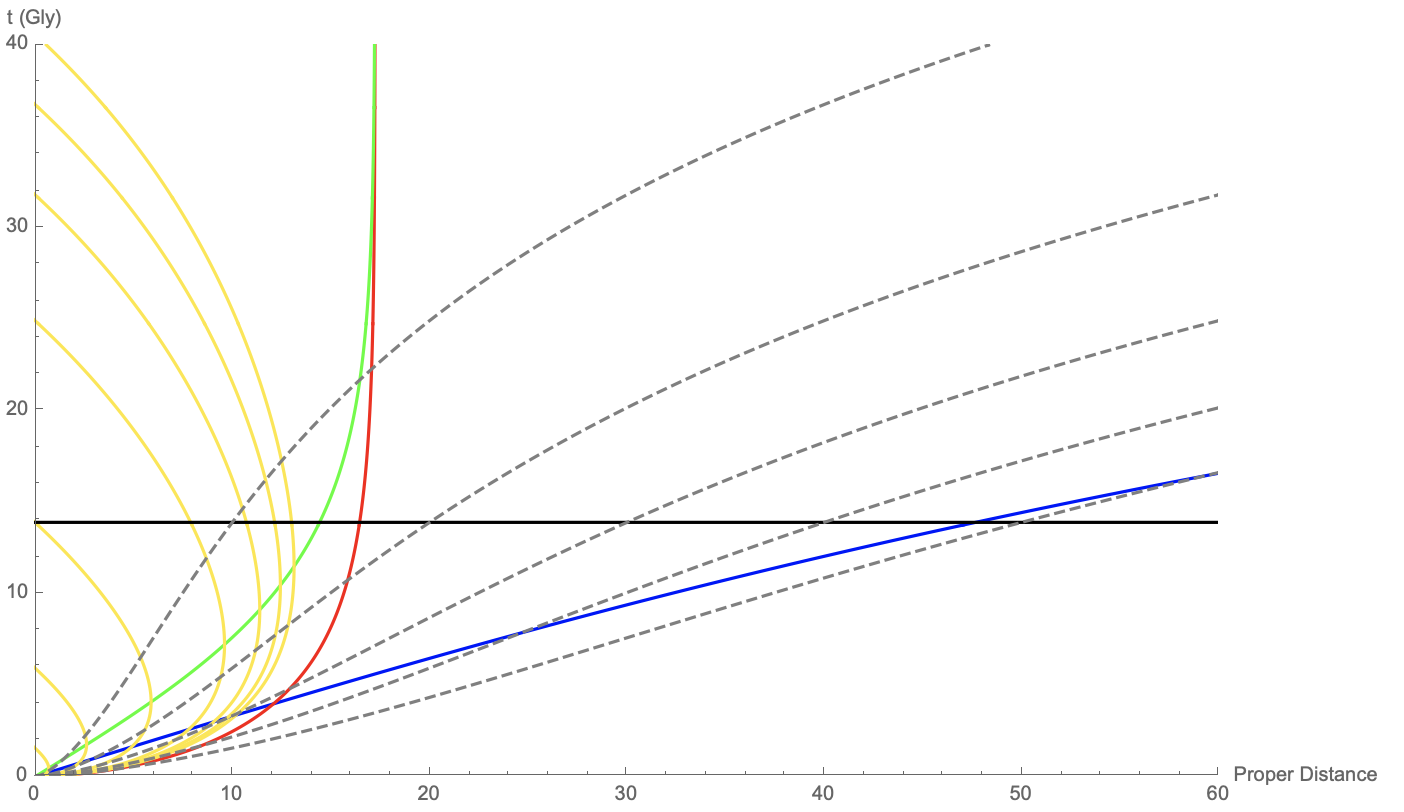

One should be extremely careful in understanding the concepts of the cosmic event horizon and the particle horizon. The cosmic event horizon is NOT the furthest distance one can see in the future. The furthest distance one can see in the future is the particle horizon in that future. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the particle horizon is bigger than the cosmic event horizon at the present and in the future. The cosmic event horizon describes the boundary beyond which the events will never be observed, while the particle horizon describes the furthest distance one can see at a certain cosmological time.

The “observable universe” is defined by the particle horizon. This is the 93 billion light-years value quoted in this wikipedia picture. According to Fig. 3, the size of the “observable universe” is getting bigger and bigger.

What the Sky Looks Like In the Far Distant Future

Because the light rays always go all the way back in time, it means that we will always in theory get photons from the objects emitted in the past. So it is not correct to say that when objects move out of the event horizon, we will never see them again. In fact, we will always see their younger selves before they move beyond the event horizon. As illustrated by the light rays in Fig. 3, as time goes on, the light ray (yellow) infinitely approaches the event horizon line (red). This means, in the very far distant future, these objects will seem to be frozen at the time when they started to cross the event horizon, and we never see them actually cross it.

As a clarification, the event horizon should not be thought of as a distance, but different distances at different times (a world line in space-time diagram), as indicated by the red line in Fig. 3. When we say the objects seem to be frozen at the event horizon, we mean, when we look out into space, the younger selves of distant objects whose light reaches us slowly approach the time when they crossed the event horizon, but never get there. Therefore, we should always be able to see distant objects as their younger selves moving closer and closer to the event horizons at corresponding times, if we still exist.

However, there’s another effect that we haven’t mentioned in this post: redshift. The wavelengths of photons emitted from the distant past will be stretched due to the expansion of space, so in the very distant future, even though we should still get photons from the distant past in theory, the large wavelengths of these photons will make it almost impossible to observe. This is the real reason why we won’t be able to these distant objects anymore, not because they already moved past the event horizon from our perspective.

Does that mean that the sky will look black in the distant future? Not if stars in our galaxy and nearby galaxies are still shining for some reason. Galaxies that are close enough to be gravitationally bound to our own when the universe expands will not be pushed away by the expansion, and could still be there. But then again, in the far distant future, stars might have already died. In that case, we won’t be able to see anything anymore.